Were Workers Entombed Within the SS Great Eastern’s Hull During Its Construction?

A November 11, 1930 article in the Lompoc Review contained an article entitled Great Eastern Surely World’s Unluckiest Ship which gave a brief summary of her history and mythology:

The first time she put to sea an explosion below the decks killed ten of her firemen. On her maiden voyage her captain fell overboard and was drowned. Next she ran on a rock and ripped open her hull. Following this, her crew seized her for their unpaid wages, she having sailed for New York prepared for 2,000 passengers and returned with 191. When the vessel was broken up the skeleton of a workman, who had disappeared mysteriously during her construction, was found wedged between the outer and inner plating of her hull.

Other disasters befell this ship.

On her launch day, she became stuck in her slip. It took three months to get her into the water.

The ship’s designer Isambard Kingdom Brunel died upon hearing of the explosion that killed it’s crewmembers.

In 1861 a storm smashed her paddle wheels and rudder.

Two cows once fell through a skylight into the ladies’ saloon.

Another time she ripped open her bottom on an uncharted rock off of Long Island.

Ultimately, the ship was a financial loss.

Background

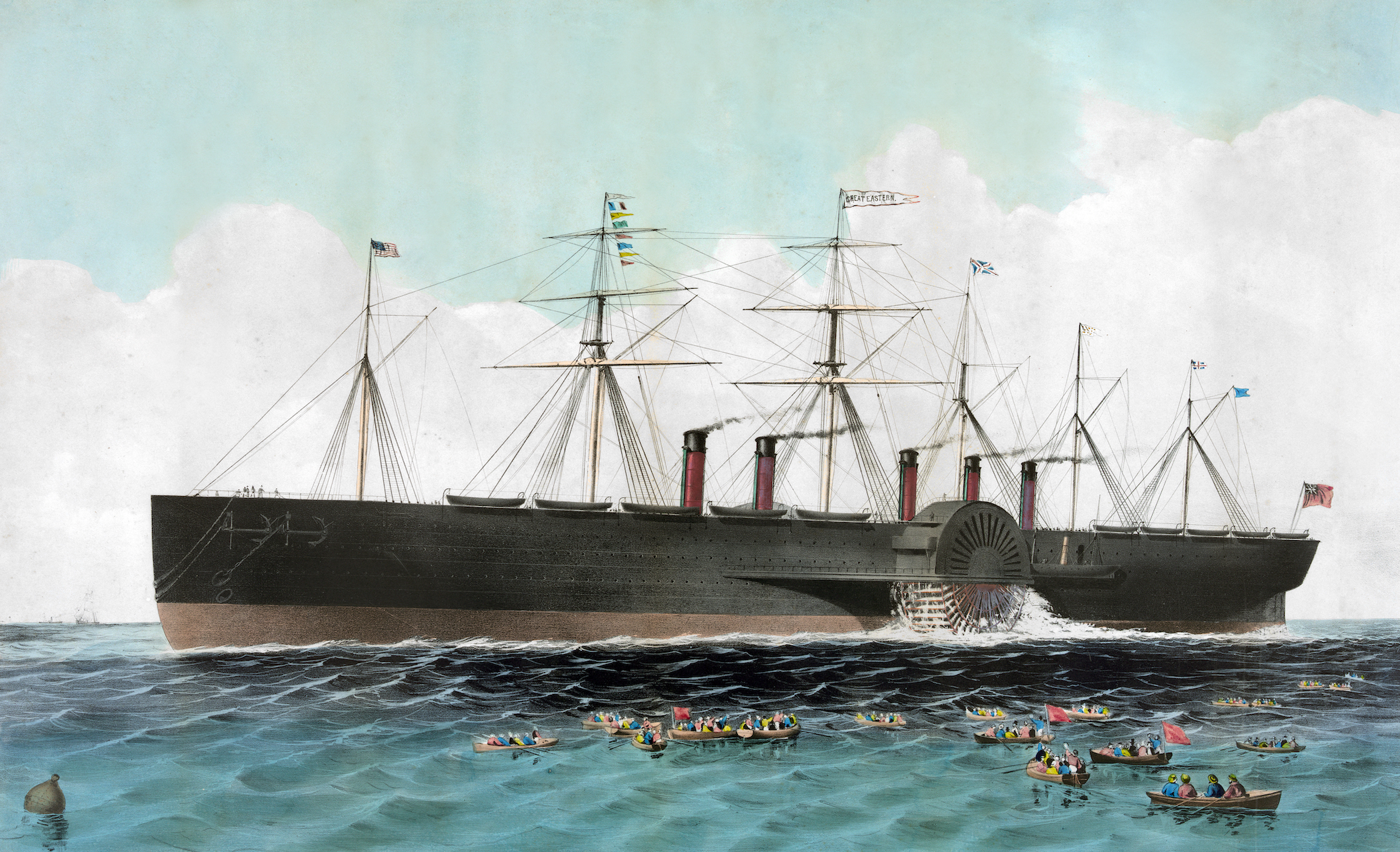

The SS Great Eastern was a passenger ship built in 1858. She was by far the largest ship of the time at a length of 692 feet and remained the largest ship for four decades until she was surpassed by the RMS Oceanic at a length of 705 feet in 1899.

The ship was designed to carry up to 4000 passengers from England to Australia without refueling. Her propulsion was provided by sails on six masts, two paddle wheels powered by four steam engines, and a single propeller powered by one steam engine.

The ship was built with a double hull (i.e. a hull within a hull to provide a redundant layer against flooding).

The ship was scrapped in 1889.

Different Narratives

There are at least three different narratives describing the person or persons entombed within the ship.

First Narrative: The Single Riveter

I first encountered the story of the entombed worker in a children’s book entitled Usborne World of the Unknown: Ghosts.

This book had a section on the SS Great Eastern entitled The unluckiest ship afloat. It described how a riveter had mysteriously disappeared during the building of the ship “as he hammered away in the hull.”

The section goes on to say:

During the first crossing, the passengers were disturbed by the dull thuds of hammering from below.

Usborne then describes what workers found while dismantling the ship for scrap:

As the workers tore into the hull, they found the remains of the riveter who had been sealed alive nearly 30 years before.

It describes how the riveter was found along with a bag of rusty tools in the one-meter gap between the inner- and outer-skins of the double hull.

This narrative is framed as a ghost story, with the ghost of the dead riveter hammering away for help. The implication is that the ship’s bad luck was caused by the ghost.

As a child reading this story, I always interpreted that the riveter was still alive during the ship’s first crossing (this seems unlikely now as I write this).

Usborne describes a similar narrative to Lompoc Review at the beginning of this write-up: i.e. that a single riveter was known to have disappeared during the construction of this ship; and that his remains were found during her destruction.

National Geographic’s Men, Ships, and the Sea describes what happened while the ship was being repaired after being damaged off of Long Island:

… workers reported a mysterious tapping within … crew members listened white-faced, for legend had it that a riveter had been sealed in alive while Great Eastern was being built.

Men, Ships, and the Sea finishes the narrative with:

In 1889 at Liverpool, the tedious and expensive job of breaking her up began. Deep inside her double hull, so the story goes, wreckers found the bones of the riveter who supposedly had jinxed her all her 31 years.

A January 1, 1864 Daily Alta California article also describes workers being frightened by the hammering and believing that it was caused by the ghost of the sealed-in riveter. Note that this article was written while the ship was still in service and long before she was broken up.

Second Narrative: A Riveter and a Smith

There is a slightly different narrative that involves two missing persons.

The August 11, 1867 Marysville Daily Appeal has the following paragraph:

There is a wild sort of a legend connected with the Great Eastern, to the effect that between the outer and inner frames or cases a smith and his riveter perished while at work and their bodies have never been found. It is said by the sailors and shipwrights that the spectres of these two victims haunt the dark space between the outer and inner cases of the vessel.

The November 30, 1867 Shasta Courier has similar story, saying:

Between the inner and the outer skins the workmen can crawl for repairs. Dreadfully dark and sepulchral, of course, it is in there, for, from the nature of the space, the workman must be completely closed in, excepting at the spot which he enters. Very few smiths or shipwrights would care to work in here alone, for two terrible spectres are supposed to haunt this place.

The article describes how almost all of the men involved in the construction of the ship believe that somewhere within the double hull lies the skeletons of a smith and his riveter. The articles says there:

… lie two skeletons which can never be found till the vessel is broken up.

Then says that during construction:

The smith was an elderly man, of a moody temper, who made no friends, and was not popular with his mates. No one had seen him leaving work; nobody was interested about him.

No one noticed that he or his riveter were missing until the next pay day when neither of them showed up.

The article finishes:

It was then soon noted that the last time they had been seen they were at work in the “case” of the ship, and before long it became a fixed notion that by a fall, or by the effect of some vapor, the two men had been killed, or stunned until closed in, and all the host of men who worked at the great ship believed that somewhere in the vast hulk there lay two skeletons, which, for some reason, could never be found.

So not only is the skeleton narrative here, but the idea that the skeletons would have to wait for the ship to be broken up (this article is written 20 years before the ship was broken up).

Third Narrative: The Missing Pay Clerk

The March 14, 1908 Blue Lake Advocate contained an article with a very different narrative:

While she was building a pay clerk sent by one of the contractors with $6,500 in wages for the men disappeared. It was not unnaturally assumed that he had bolted with the money. His wife and family were left unprovided for, with the stigma of his supposed crime upon them.

The article continued:

While she was being taken to pieces the ship breakers discovered between her inner and outer casings of steel the skeleton of a man. Papers which had fallen from his clothes enabled his identity to be traced. It was the skeleton of the pay clerk who thirty years before had disappeared.

How did the pay clerk end up within the hull of the Great Eastern? The article provides an explanation:

There was no money; that was never recovered. The supposition is that the poor fellow on going on to the ship was pounced upon by workmen who knew that he had the money with him; that they stunned him and, having a small place in the side of the vessel to complete, crammed his body in and built him up in it.

This story was printed nearly a decade after the Great Eastern had been broken up.

Also, it paints the picture of a murder mystery rather than a tragic accident.

Analysis

Based on the newspaper articles I’ve referenced, it’s clear that it was believed that one or two skeletons were entombed within the SS Great Eastern. It’s not clear when that started – i.e. while the ship was being built; or when the ghostly hammering sound was heard while it was being repaired. But it did begin early in the ship’s career.

Men, Ships, and the Sea does offer an explanation for the ghostly tapping:

A worker found that the hammering came from underwater tackle.

The January 1, 1864 Daily Alta California article says:

A diver said he heard him hammering at the bottom of the ship, and the fear was universal until it was discovered that a swivel connected with the moorings worked to and fro, the movement causing a chink or vibration which at times, more especially at night, was heard throughout the vessel. It was this sound which had conjured up the phantom.

Questions

- Do you believe bodies were entombed inside of the SS Great Eastern?

- Why the different narratives?

- How do such narratives originate and get attached to historical events?

Credits

Great Eastern by Bill Glover

https://atlantic-cable.com/Cableships/GreatEastern/index.htm

SS Great Eastern Wikipedia Page:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Great_Eastern

November 11, 1930 Lompoc Review article Great Eastern Surely World’s Unluckiest Ship:

National Geographic Men, Ships, and the Sea by Alan John Villiers

https://www.amazon.com/Men-Ships-Sea-Story-Library/dp/0870440187

Usborne World of the Unknown: Ghosts

https://www.amazon.com/World-Ghosts-Various/dp/1474976689

January 1, 1864 Daily Alta California article:

August 11, 1867 Marysville Daily Appeal article:

November 30, 1867 Shasta Courier article:

March 14, 1908 Blue Lake Advocate article:

Extra Links

MotorBoating Magazine February 1967

The Atlantic Telegraph by William Howard Russell